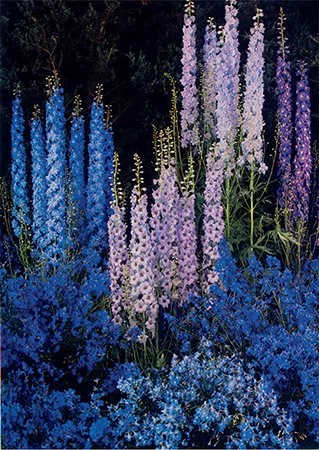

Objective intelligence can perhaps best be described as the way a body “stylizes” its being—the formalizations through which it presents itself to us. It serves no biological function, generates no meaning, and has no higher authorization. It is the formal pattern or design through which an object presents itself—the “composition” that it might be said to “perform,” for the “beholding eye” of the viewer who is “presupposed” by its pattern or form. This intelligence is what inspired Eugene Delacroix to call the human body an “admirable poem,” prompted the French Surrealist writer Roger Caillois to say that there must be “an autonomous aesthetic force in the world of biology,” motivated the American photographer Edward Steichen to curate an exhibition of delphiniums at MoMA in 1936, and impelled me to devote a chapter of World Spectators (2000) to the “language of things.”

Objective intelligence also informs every aspect of Aby Warburg’s historiography, and it inspired the German sculptor and photographer Karl Blossfeldt to describe a plant as an “architectural structure, that has been shaped and designed ornamentally and objectively,” and to posit these structures as the source of human art-making—to argue that the “fluttering delicacy of a Rococo ornament, the heroic severity of a Renaissance candelabrum, the mystically entangled tendrils of the Gothic flamboyant style,” and the shapes of wrought-iron railings, all “trace their original design back to the plant world.”

Edward Steichen, Delphiniums, 1940. Dye imbibition print. Digital image courtesy of the George Eastman Museum. © 2019 The Estate of Edward Steichen/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

(Please cite kajasilverman.com when reproducing this passage.)